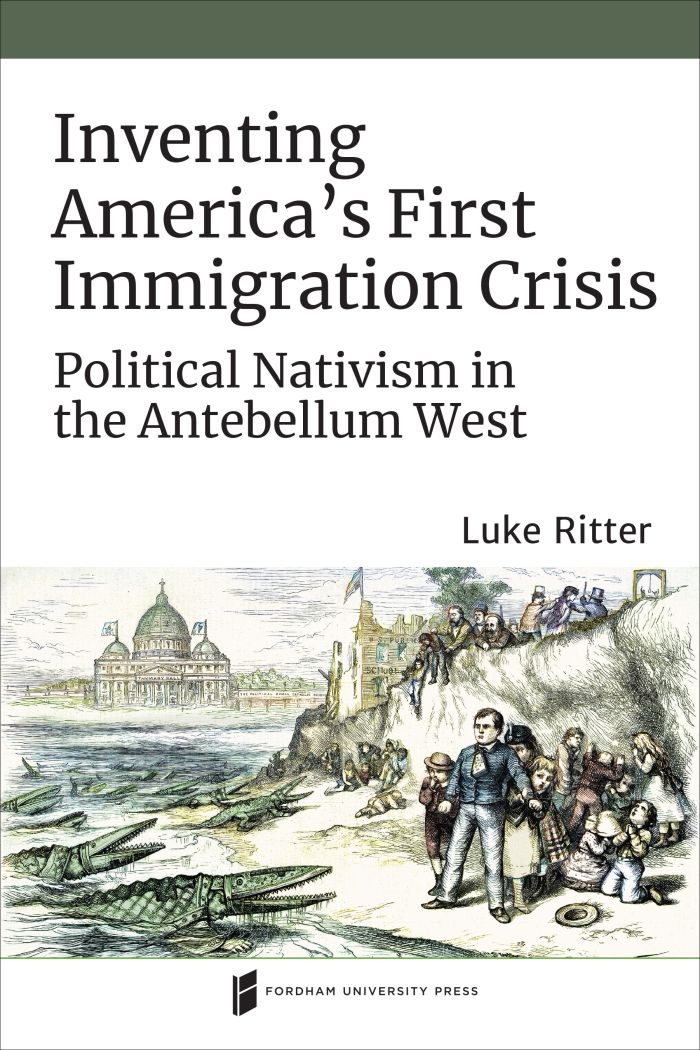

Inventing America's First Immigration Crisis

Political Nativism in the Antebellum West

This book can be opened with

Why have Americans expressed concern about immigration at some times but not at others? In pursuit of an answer, this book examines America’s first nativist movement, which responded to the rapid influx of 4.2 million immigrants between 1840 and 1860 and culminated in the dramatic rise of the National American Party. As previous studies have focused on the coasts, historians have not yet completely explained why westerners joined the ranks of the National American, or “Know Nothing,” Party or why the nation’s bloodiest anti-immigrant riots erupted in western cities—namely Chicago, Cincinnati, Louisville, and St. Louis. In focusing on the antebellum West, Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis illuminates the cultural, economic, and political issues that originally motivated American nativism and explains how it ultimately shaped the political relationship between church and state.

In six detailed chapters, Ritter explains how unprecedented immigration from Europe and rapid westward expansion re-ignited fears of Catholicism as a corrosive force. He presents new research on the inner sanctums of the secretive Order of Know-Nothings and provides original data on immigration, crime, and poverty in the urban West. Ritter argues that the country’s first bout of political nativism actually renewed Americans’ commitment to church–state separation. Native-born Americans compelled Catholics and immigrants, who might have otherwise shared an affinity for monarchism, to accept American-style democracy. Catholics and immigrants forced Americans to adopt a more inclusive definition of religious freedom.

This study offers valuable insight into the history of nativism in U.S. politics and sheds light on present-day concerns about immigration, particularly the role of anti-Islamic appeals in recent elections.

Luke Ritter provokes his readers to consider the surprising origins of our modern-day understanding of church–state separation, rightly seen by many as essential to ‘diversity,’ ‘inclusion,’ and ‘tolerance,’ in the sometimes rabid intolerance of the nativist movement in antebellum America. To do this, he invites scholars who have focused primarily on nativism in the Northeast (and only recently in the South) to turn their eyes west. It was in the West, he tells us, that rank religious bigotry was transformed into a higher ideal that is used by advocates on both the left and the right to defend religious freedom today.—Maura Jane Farrelly, author of Anti-Catholicism in America, 1620–1860

Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis is a much-needed addition to scholarship on nativism in the United States that concentrates on its manifestations in the Trans-Mississippi West. Ritter illuminates regional distinctions and contexts that historians—myself included—have all too often overlooked in ‘flyover’ scholarship that implicitly or explicitly claims that nativist expressions in northeastern cities are representative of the movement writ large. By probing unique and regional primary sources, Ritter attends to the broader contexts of increasing immigration, expansionism, and evangelicalism as well as the particular media and strategies employed by nativists to illustrate how their ideologies circulated in the urban midwestern United States. Crucially, by concentrating on those regional distinctions, Ritter is able to give immigrants agency, whether as early settlers of rapidly growing cities and neighborhoods, mobilizers against Sunday laws, or co-creators of a distinct and more inclusive—if also necessarily more generic—civil religion. What’s more, in Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis, Ritter illuminates the deep contradictions in nativist strategies and how they drove its adherents to become precisely what they mistakenly feared immigrants inherently were: insular, anti-democratic, and violent. Last, this text is a trenchant reminder that current global and national ideologies are as much as—if not more than—trope as trend. Students and scholars in American history, religion, and political science (to name just a few) will find Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis a necessary and key addition to their library.—Katie Oxx, St. Joseph’s University

Luke Ritter's Inventing America's First Immigration Crisis couldn't be more topical. Just in time for the Capitol Insurrection of 2021, Ritter's book unearths events like the Cincinnati Election Day Riot and Chicago Lager Riot of 1855, both triggered by the fear that illegal undocumented voters would seize power from the rightful constituents of the American republic. The MAGA hordes of the Trump years find their parallel in the Know-Nothings, the secretive, conspiracy-fueled brotherhood that channeled wide popular support into electoral success as the American Party... Inventing America's First Immigration Crisis is a fascinating, readable, fact-packed exploration of motifs in American culture that show no signs of going away. It may not explain why the animosities of the 2020s persist, but Ritter definitely shows that they are no new thing.—Timothy Morris, University of Texas at Austin

Inventing America’s First Immigration Crisis is an impressive, important book . . . Given that we are living in an era characterized by more anti-immigrant violence than at any time since the heyday of the Know Nothings, Ritter’s message is one that Americans need to hear now more than ever.—Tyler Anbinder, Missouri Historical Review

Introduction | 1

Chapter 1

The Valley of Decision | 9

Chapter 2

Culture War | 31

Chapter 3

The Power of Nativist Rhetoric | 60

Chapter 4

The Order of Know-Nothings and Secret Democracy | 82

Chapter 5

Crime, Poverty, and the Economic Origins of Political Nativism | 105

Chapter 6

From Anti-Catholicism to Church-State Separation | 148

Epilogue

The Specter of Anti-Catholicism, New Nativism, and the

Ascendancy of Religious Freedom | 174

Notes | 185

Index | 251